Our digital self – our digital health

What self-tracking can tell us?

Knowing our bodies means knowing ourselves. It is very natural for humanity to try to get deep insight into the body. We are constantly measuring, testing and improving it. Nowadays with the arrival of the new technologies, measuring and quantifying ourselves became very simple. Since the emergence of self-tracking devices, the “new culture of personal data” 1 has appeared leading to a revolution of individual’s understanding of own body.

Release of FitBit in 2008 caused a sharp growth in the popularity of wearable tracking devices that are promoting the concept of self-knowledge through self-monitoring, self-measuring, self-reflection and finally self-improvement. There is a range of parameters that self-tracking devices and applications are measuring. Most often it is weight, heartbeat, stress levels, sleep phases or physical activity like walking or running. Nevertheless, amongst all the measurements offered there was a deficiency of certain parameters, namely for female-body tracking. A few years ago the gap was noticed and femtech – technology designed for women started developing dynamically.

“Femtech,” a term coined in 2016 by Ida Tin, the founder of period- and fertility-tracking app Clue, refers to technologies and products that are designed for women’s health. This includes businesses focused on period care, pregnancy, childbirth, aging, menopause, fertility management and sexual health.

BakerHostetler

In the era when people are “googling” the symptoms of a disease before consulting a doctor, giving a part of trust to a health-oriented application is easier and comes naturally. People are more prone to give up personal details to a device. The data is flowing, and it is flowing in large quantities. Out of the data, the question emerges: what can we learn from this data? can we draw conclusion out of the enormous datasets and really learn about the health? can we make it useful for reliable medical and sociological research? What does it imply for the individual users of the apps as well as for the female and male population?

Reflecting on these questions, this essay will give an account of the emergence of the technology for women’s health (taking menstruation tracking application as a precise example) and its position in the digital health space. It will also try to analyse how femtech redefines approach towards women’s health.

The paper will also focus on the way the applications collect our data and observe our very personal practices in details. It will examine what kind of data is being collected, what can it possibly bring into the research for sociology and health, and what methodological issues it may arise or already has.

The aim is to investigate whether the self-tracking applications really allow us to learn about the society in the way they claim. It will reflect on what self-tracking has changed in individual practices if it comes to body and health and how it then changes the way to understand this new practices.

The rise of femtech

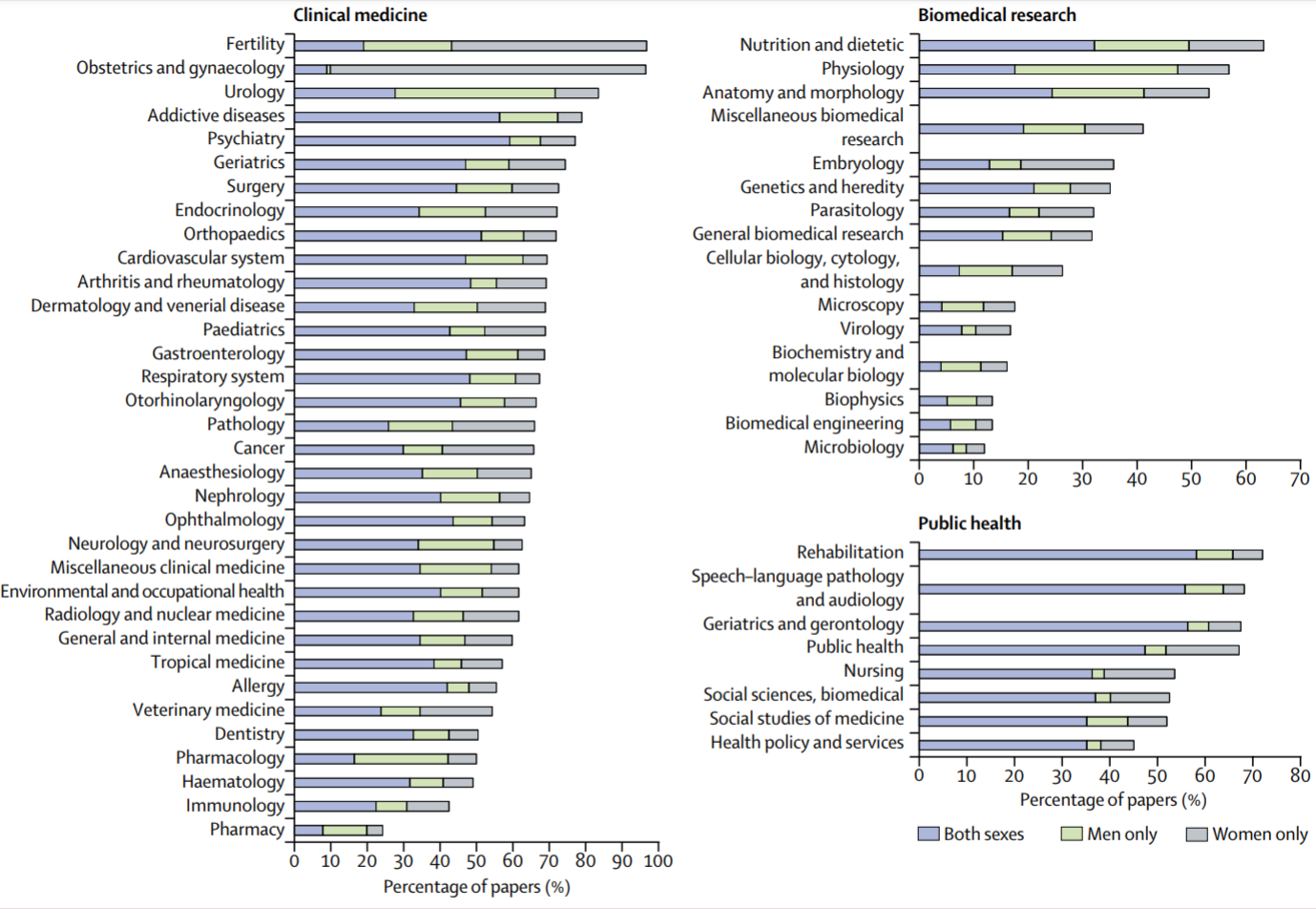

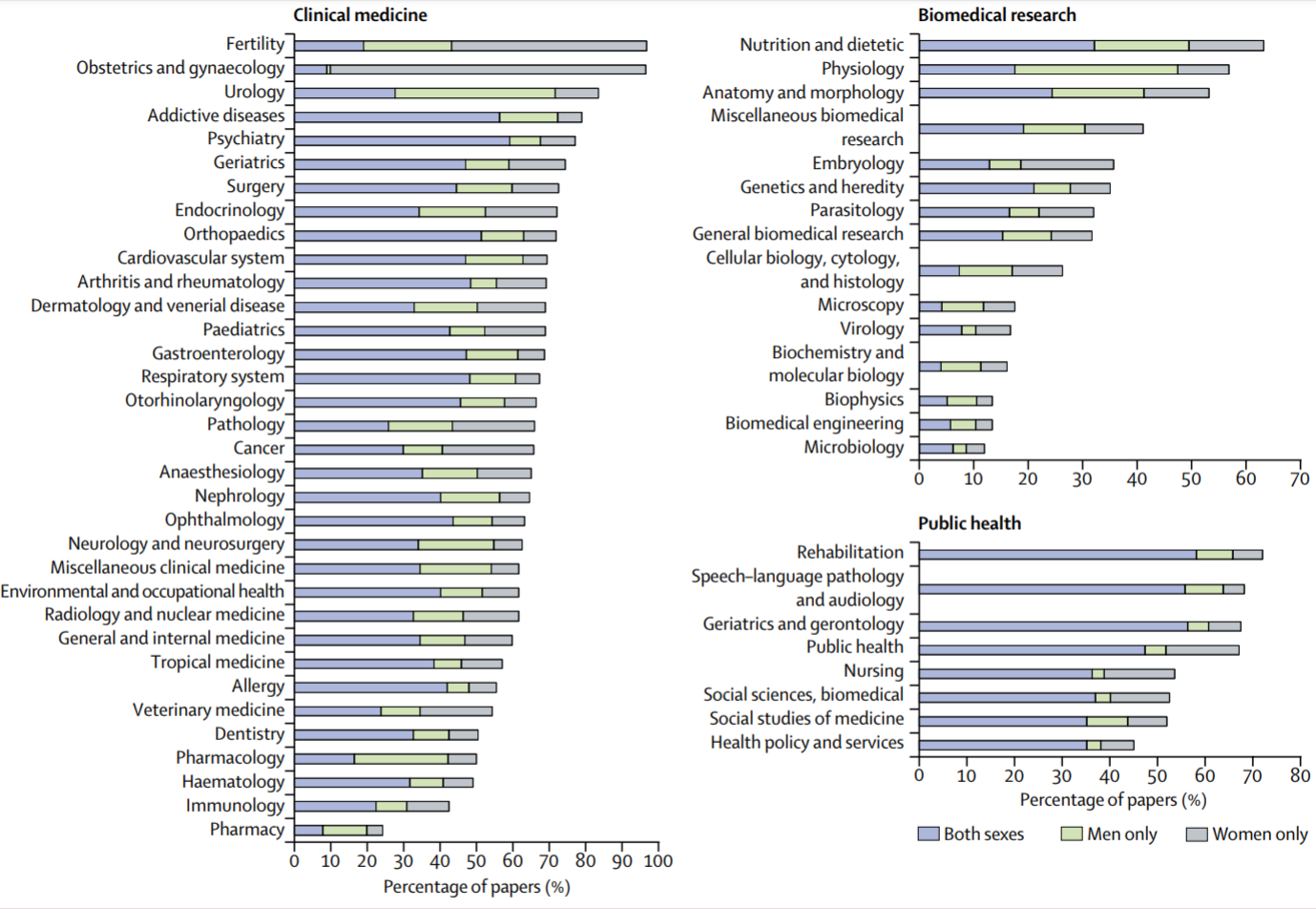

Just a few years ago the global research was lacking insight into areas of female heart disease and gynaecological disorders. Research published by The Lancet shows that women have often been underrepresented or excluded from the medical research, despite research studies showing sexual dysmorphism on genetic, cellular, biochemical and physiological levels.

The lack of female participants in the research was mostly justified by inconsistency caused by female oestrous cycles. Technology designed for women before 2016 was considered as a niche market. It is clear that there is a big data gap that could be filled. This fact was noticed by numerous entrepreneurs in the field of digital health.

Since 2016 the situation has begun to change and products and technologies designed for women now are having a boom. After the wearable tracking devices, the time has come for the period-tracking applications. In 2017 the interest around the Femtech has skyrocketed. Femtech market is rising very fast and expected to increase to $50 billion by 2025, reports The Guardian. Nowadays, the industry consist of around 200 startups all over the world, managed principally by female innovators.

As an example for femtech analysis we will take period tracking applications. They can be divided into three main types: period-tracking, fertility and contraception.

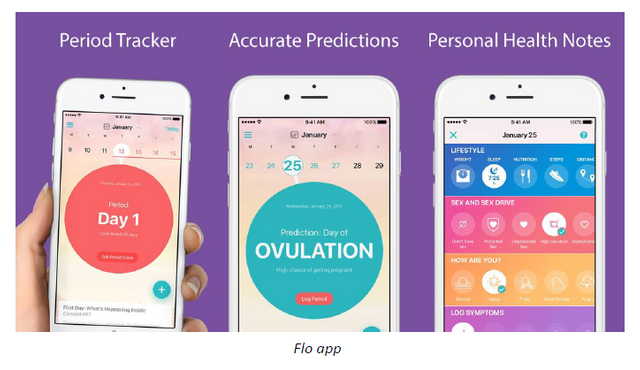

Let’s take few most popular under the scrutiny. The basic line for all of them is giving an ability for the user, to register the dates and intensity of menstruation. Above all that, app like Clue enables to enter a waste range of data, from cervical mucus type to condition of the hair. The entered data can be downloaded and send to a doctor, pushed on an Apple watch, Fitbit or shared with others.

The most popular application so far is Flo. It was downloaded by 110 million of women worldwide. and used actively by 30 millions of women. Next to the standard period-oriented data it logs also weight, sleep, water intake, mood, headaches and alcohol intake.

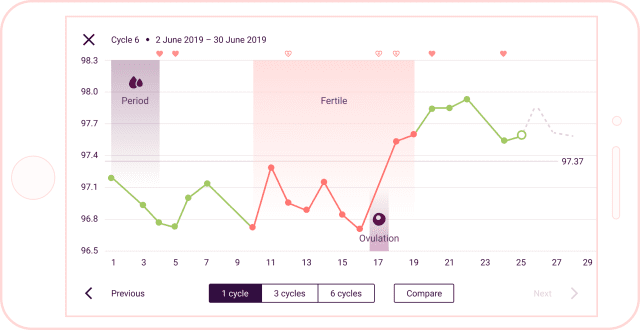

Natural Cycles is the only one that additionally measures basal body temperature (BBD) and then uses an algorithm to predict fertility days. The application is also the only one to be officially certified as a form of “digital contraception” in Europe in 2017, after getting the approval from Food and Drug Administration (USA) to market itself as a contraception. This approval seems to be taken rather lightly, given the fact that Natural Cycles received a backslash after the application was referred to Swedish authorities as a cause of numerous unwanted pregnancies and what follows, abortions . Marketing Natural Cycles as “highly accurate” turned out to be an overestimation.

The innovators claim to focus on women’s well-being and improve it thanks to data analysis. Except for period tracking and fertility days prediction, the applications offer multiple benefits: Flo is offering “daily health insights” and discussion over different health topics. Natural cycles puts freedom and control at stake and promises the users to “take control over your body, fertility, sex, life and cycle” and Clue promises help in understanding of your own body. The applications offer not only improvement of one’s health, but also a space for social interaction.

New application, new space for interaction

In the Internet age, social interactions are being constantly modified, and so are ways of studying them. New methodologies are needed. We are constantly connected, it’s hard to tell apart when we are really “offline” or “online”, the boundaries between virtual and real are blurred. 2

“New ways of using and interacting with digital technologies have fundamentally changed the ways we think about the ”space ” of online interaction and experience”

Deborah Lupton, « Digital Sociology«

Researcher Boris Beaude proposed a new term for describing creation of common time and space for the interaction – synchorisation.

« Synchorisation -c’est-à-dire le processus par lequel nous produisons du lieu en commun pour être et pour agir, processus par lequel la distance devient moins pertinente, processus par lequel l’interaction devient possible »

Boris Beaude, « Les virtualités de la synchorisation »

The geographical distance is reduced as never before, giving the opportunity to interact with anyone on the planet in the real time. Even if creating social networks is not the main aim of period-tracking apps, they give the users possibility to interact and create communities. They modify geographical distances between societies, facilitating dialogue.

Likewise, the relation patient – doctor became different. One thing is, that often the first diagnose we get, comes from what we can “google”. And even if we decide to confront our “google doctor” with the one with the diploma, we can present a history of our activities, all thanks to self-tracking.

Discussing our health issues with others may be reassuring. The innovators of tracking apps knew that and designed a space for potential social interactions. Application like Flo offers a possibility to participate in a new community, discuss intimate topics and get support from other women. That creates the communities where, topics like menstruation can be discussed without limits. This is an important feature, when still, in many cultures, it is a taboo subject. Even in western, developed countries, like Great Britain, more than a half of women aged 16-24 is ashamed by talking about periods, found a study mentioned in Independent. Disapproved topic of menstruation has equally impact on work and school. The study found that 75% out of 3.5 million of women who took a day off because of their periods, were hiding the real reason behind their absences. When we look at the numbers, we can see that menstrual phase a big impact on functioning of the single woman and society.

The new space for discussion created by these applications can have a very good impact on taboo-breaking around women’s health (menstruation, pregnancy, breastfeeding, depression, sexuality and more).

« People are embarrassed talking about periods, but this app makes them seem less of a shame and more of a way of life. It is a reminder that all women go through the same thing and no one should ever feel embarrassed about it. For my friends and I it is just another way for us to become closer, while also having a bit of a laugh » we can read a young user’s opinion in The Guardian.

The “virtual” space has a potential of impact on the territorial space in many countries. It can raise the discussion about women’s health and awareness about understudied or omitted issues.

The endless opportunities

The aims and promises of the applications are clearly stated: giving personal insight into one’s body, measuring reactions of the organism during cycles, giving feedback about the state of the health and giving the opportunity to join a community for an open discussion. The general aim, as stated by developers, is to improve quality of women’s health worldwide and increase their presence in scientific research.

Self tracking app could provide accessible data to evaluate evolution of menstrual health, which is an important indicator of women’s overall health status. 3

The applications could actually work as an education source about female health issues and STDs prevention. Especially in the places with poor access to education and scarce medical care. Thanks to their power of data collection they could also contribute to gathering data about obstetrics and gynaecological diseases or disorders, help to diagnose them or find links between menstrual cycle and other diseases, like for example eating disorders or migraines. The data can also be used to combat health conditions that occur more in female population, like Alzheimer, osteoporosis, anxiety and more.

The opportunities are endless. But the question is how should we study the data ? It needs to be remembered that the majority of the app users are white, european or north-american women. 4 There is a risk of generalization. What about the other ethnicities, or those who don’t have every day access to the smartphone? The applications are also not always suitable for people touched with some medical conditions like endometriosis, remarks Marion Police in Le Temps. Nonetheless we need to remember that never before did we have such a great opportunity to study menstrual cycles.

Personal, private? Where is the border ?

The benefits we can draw from the collected data are clear. Quantifying ourselves could shed light on understudied medical issues. But how quantifying ourselves influences our private life?

With the times changing, the definition of personal and private is shifting. It is possible to expose our privacy and give up the most sensitive data without directly exposing our face, remarks researcher Boris Beaude:

« Alors que nous n’avons jamais été aussi informés, la vérité vacille. Alors que nos corps sont de moins en moins exposés directement, la vie privée est profondément perturbée. Alors que notre quotidien est de plus en plus « anonyme », le droit à l’oubli devient un enjeu majeur. «

Boris Beaude, « (re)Médiations numériques et perturbations des sciences sociales contemporaines »

We’re exposing data about our body. Through measuring and quantifying we are creating an extension of ourselves, a digital body, stored in a cloud. It becomes a part of a bigger, digital organism. And everybody knows, that once we’ve put something online it’s very likely to never disappear. We are also facing the issue of centralization of internet and data by huge companies, like FAANG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google). According to investigation of Privacy Policy run in December 2018, 61% of the most popular applications in Google Play Store send data to Facebook the second they are opened. Investigation was repeated in March, with reassuring better results, but it doesn’t mean we can be negligent of the life cycle of data we expose. And if revealing that we’ve looked for a flight to Rome is maybe less sensitive, sharing information about our fertility status, sexual life or attempts to get pregnant is a different thing. When it comes to big data, our privacy is at stake. With big data analysis, new frameworks for research are needed in order to protect sensitive personal data.

What kind of data are we sharing?

Millions of women worldwide were discreetly noting the dates of their periods in calendars or notebooks. Now, thanks to the technology it is possible to do it in the device that we always have on us. This is very convenient, we stock all the information in one, at-all-times-accessible device. The application not only remembers the dates, but also gives feedback and predicts the state of our body. Storing data in our smartphone seems very personal and discreet, but is it ?

Flo admits to have collected over 13 billion data points and has a team of 15 data scientist working on it. They have more data than a team of medical professionals can collect throughout whole carrier.

Let’s take a closer look at the period tracking apps functionalities. It is clear that they make up a huge dataset with many details. They measure a vast range of factors:

- ① Menstruation prediction control, checking

- ② Ovulation prediction checking

- ③ Basal body temperature

- ④ Making note of specific physical condition

- ⑤ Diet functionality such as weight control

- ⑥ Predictive Notification for next menstruation

- ⑦ Cycle extent education (information about sleepiness, irritation, etc.)

- ⑧ Health log (food, feeling, Sex drive status)

- ⑨ Symptoms (headache, digestion)

- ⑩ Sexual activity

- ⑪ Medication log

- ⑫ Fertility assistance

- ⑬ Information, Q&A, articles

- ⑭ Messaging and chat in app

- ⑮ Physical training program when pregnant

- ⑯ Emotional mood

- ⑰ Pill diaries

- ⑱ Vaginal condition (vaginal secretions) 5

Quick look at the functionalities and we can say right away that many of them we share only with the closest people around us or we do not share at all. A question arises: is this highly intimate and sensitive data necessary or helpful during a standard doctor visit? Maybe yes. Does someone except for medical professionals and closest people needs to know such details ? Probably not. We need to remember that mobile applications don’t have to meet the privacy standards of hospitals or medical professionals. We give up highly sensitive information but do we know the life cycle of the data once we enter them into the applications? How transparent are the applications about their privacy policy?

In the article by Lauren Sharkey, Clue’s spokesperson says that their business model is based on transparency and privacy policy is intelligible. Flo also claims to be very open about its data practices, and Glow clearly states that they do not sell or rent any personal data to third parties. And the investigation run by Privacy International indeed confirms that not Flo nor Clue share data with Facebook, which is very good news. Glow does not sell data, that it is true, but it does not exclude sharing information drawn from the data with third parties for business purposes. 6 It is not very clear for what the data could be used, medical research or maybe marketing? Before installing the application, we should verify if the privacy policy is acceptable and how much of the personal info we agree to share.

Are digital devices really allow us to learn about our bodies in the way they claim?

Noortje Marres in her book 7 argues that digital ways of knowing society should be studied in broader spectrum. According to Marres, huge attention is given to the ethical and political issues and it clearly justified. Nevertheless, in the same time, we need to focus more on the question whether the digital devices and application really can teach us about society in the way they claim?

Digitization of the world has modified our practices and behaviors. The society can be studied via digital tools but the digital tools are at the same time modifying the society. There is a continuous loop. Human being is unpredictable and unstable. Digitization accelerates the flow of information which has its pros and cons – it is easier to gather information about huge group of people in relatively short time, and some may say it is a gold mine for sociological research, but fast flow of information also accelerate changes and we need new tools for the research.

The earlier elaborated frameworks for conducting social research are not always applicable in digitized world. Marres reminds, that established frameworks of research ethics are different for big data analysis, and using inadequate frameworks has already risen many problems in terms of lack of consent or harmful exposure.

We should reflect on the digital ways of knowing society. How does observation and analysis of our practices actually changes our practices? Is quantifying our body modifying our behavior ? Will we modify our behavior in order to reach better results ?

The fact that we are being observed, even if not directly, has an impact on our us. When we’re measuring ourselves we can get a precise tracks of our body’s improvement, we can make analysis and compare it with others. We may try to meet the standards that are not reachable in the particular moment of our life, or conditions we’re living in. Professor Lupton, who researches women’s use of technology, remarks that not all the apps are suitable for all states of our body. Not all of the device functionalities were designed to track heavily pregnant bodies or people taking care of a newborn baby. Our body’s underperformance at those moments is normal, nonetheless seeing the perturbations compared to our previous results may cause an unnecessary feeling of guilt or anxiety. Or we may actually wait for the numbers and device to tell us how to feel?

Some loyal users of self-tracking devices set up the community of Quantified Self – aiming to know themselves via numbers.

« The Quantified Self is an international community of users and makers of self-tracking tools who share an interest in “self-knowledge through numbers.”

Electronic devices became integral part of our life. Self- tracking, used all day, all night long devices are becoming an extension of our bodies, extension of ourselves. Lupton says, that we are becoming cyborgs. Lupton’s digital cyborg is

“the body that is enhanced, augmented or in other ways configured by its use of digital technologies, that are worn, carried upon or inserted in to the body continually interacting with these technologies in dynamic ways” 8 Digital technologies become the extension of our bodies, and somehow, also ourselves. We can have very intimate relationships with the devices and maybe we confide in them more than in anyone else. They are becoming an inseparable part of our lives, modifying our everyday life.

Conclusion

There is still a lot to discover and learn about our bodies and its functionalities. Self tracking applications and devices offer us insight into our bodies, and through that knowledge about ourselves. We can become better, quantified version of ourselves, more aware of our body’s state. And when health steps up into the game, knowing our body’s history and tracking its behavior becomes essential for our well-being. We can also share with others, create online (and not only) communities, and easily discuss with others.

Self tracking is becoming more and more present in our life, we want to know how much steps we’ve taken, how much calories have we eaten or have an overview of the menstrual cycle. Devices keep us company day and night and register huge amounts of details, sometimes highly sensitive and very personal ones. They are changing the way we’re living and percepting the world. They also modify our behaviors and social interactions.

While they’re becoming an integrated part of our life they are collecting enormous amounts of data about our practices. And that may be a positive fact, the dataset collected by the health tracking devices is probably much bigger than many hospital’s ones. Thanks to correct analysis of the data it is possible to find patterns and links between health conditions that could not be found otherwise. We have possibility to fill still existing knowledge gaps and improve health standards of numerous people.

Nonetheless, with big data analysis, big problems come along. Problem of the accessibility and legality of the data, consent issues and exposure of sensitive data. The big companies that will want to monetize our sensitive data, bombarding us with advertisements via all digital channels possible.

In order to really exploit potential of the big data, we need new frameworks of study, whether it is for medical or sociological purpose. It is important to reflect on how should we study the data, on what purpose, who should have access to it. Big data can provide us with new ways of knowing society, but it should be approached on all ethical, political and epistemological levels.

References

Beaude, Boris, “Les virtualités de la synchorisation.“ Pré-Print in Géo-Regards, Mobilités et gestion des flux à l’ère du numérique, dir. Sarah Widmer, Silvana Pedrozo et Francisco Klauser, n°7.

Beaude, Boris, “ Spatialités algorithmiques” , in ROMELE, Alberto et SEVERO, Marta (dir.), Traces numériques et territoires, Paris, Presses des Mines, 2015, pp 133‑160.

Beaude, B. (2017). “(re)Médiations numériques et perturbations des sciences sociales contemporaines.” Sociologie et sociétés, 49 (2), 83–111.

Crawford, Kate, et al. “Our Metrics, Ourselves: A Hundred Years of Self-Tracking from the Weight Scale to the Wrist Wearable Device.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 4–5, Aug. 2015, pp. 479–496,

Davis, Nicola.“Natural Cycles app: ‘highly accurate contraceptive’ claim misled consumers” Guardian, 2018. Online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/aug/29/natural-cycles-app-highly-accurate-contraceptive-claim-misled-consumers

Gander, Kashmira. “The Period Tracking Apps Helping Millions of Women Manage Their Menstruation.” Independent, 2016. Online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/period-tracking-apps-best-clue-flow-pink-pad-menstruation-flow-fertility-cramps-pms-a7365356.html

Kresge,Naomi., Khrennikov, Ilya., Ramli, David. “Period-Tracking Apps Are Monetizing Women’s Extremely Personal Data” Bloomberg Businessweek, 2019. Online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-24/how-period-tracking-apps-are-monetizing-women-s-extremely-personal-data

Lupton, Deborah. Digital Sociology. Routledge, 2015. pp. 164-191

Gabriel, Jessie., Ravi, Tara. 2019. “Women Investing in Women’s Health: The Rise of Femtech Companies and Investors in Celebration of Women’s History” Online: https://www.bakerlaw.com/alerts/women-investing-in-womens-health-the-rise-of-femtech-companies-and-investors-in-celebration-of-womens-history-month

Marres, Noortje. Digital Sociology. The Reinvention of Social Research. 2017

Miyamoto, Maki., Pau, Louis-Francois. « Can Female Fertility Management Mobile Apps Be Sustainable and Contribute to Female Health Care? Harnessing the Power of Patient Generated Data: Analysis of the Organizations Active in This E-Health Segment. » 2018. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3256817.

Police, Marion. “Quand femtech et recherche scientifique s’associent.” Le Temps. 2019. Online: https://www.letemps.ch/societe/femtech-recherche-scientifique-sassocient

Sharkey, Lauren. “Is The Rise Of Femtech A Good Thing For Women? Here’s What The Experts Think. ” Bustle, 2019. Online: https://www.bustle.com/p/is-the-rise-of-femtech-a-good-thing-for-women-heres-what-the-experts-think-17993009

So, Adrienne. “The Best Women’s Health Apps, Period” Wired, 2018. Online:https://www.wired.com/story/best-womens-health-apps-2018/

Sugimoto , Cassidy R., Ahn,Yong-Yeol., Smith, Elise.,Macaluso, Benoit., Larivière, Vincent. “Factors affecting sex-related reporting in medical research: a cross-disciplinary bibliometric analysis” Lancet 2019; 393: 550–59

Symul, Laura.,Wac, Katarzyna., Hillard, Paula., Salathe, Marcel. “Assessment of Menstrual Health Status and Evolution through Mobile Apps for Fertility Awareness”, 2018

Woodford, Isabel “Digital contraceptives and period trackers: the rise of femtech” Guardian, 2018. Online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/oct/12/femtech-digital-contraceptive-period-trackers-app-natural-cycles

Notes

- Crawford, Kate, et al. “Our Metrics, Ourselves: A Hundred Years of Self-Tracking from the Weight Scale to the Wrist Wearable Device.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 4–5, Aug. 2015, pp. 479–496, doi:10.1177/1367549415584857 Our metrics, ourselves : p 480

- Lupton, Deborah. Digital Sociology. Routledge, 2015. pp. 164-191

- Symul, Laura.,Wac, Katarzyna., Hillard, Paula., Salathe, Marcel. (2018) “Assessment of Menstrual Health Status and Evolution through Mobile Apps for Fertility Awareness” 10.1101/385054.

- Symul, Laura.,Wac, Katarzyna., Hillard, Paula., Salathe, Marcel. (2018) “Assessment of Menstrual Health Status and Evolution through Mobile Apps for Fertility Awareness” 10.1101/385054.

- Miyamoto, Maki & Pau, Louis-Francois. (2018). « Can Female Fertility Management Mobile Apps Be Sustainable and Contribute to Female Health Care? Harnessing the Power of Patient Generated Data: Analysis of the Organizations Active in This E-Health Segment. » SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3256817.

-

« We may decide to share information about your transactions and experiences using the Glow Service (but not about your creditworthiness) to our affiliates for their everyday business purposes. »

“Unless you request the deletion of your personal information and subject to applicable law, Glow maintain copies of your content indefinitely, even after you terminate your account.” at: https://glowing.com/privacy

- Marres, Noortje. Digital Sociology.The Reinvention of Social Research. 2017, Chapter 6 « Does digital sociology have problems? »

- Lupton, Deborah. Digital Sociology. Routledge, 2015. pp. 164-191